in Story & News

The Silence of the Concert Hall:

How the Identity

of Public Music Venues Has Evolved

You burst into applause after a grand first movement at a classical concert, but fall into embarassed silence as your neighbors give you a reproachful look. Or perhaps you’ve struggled to make sense of the musical program in the dim concert hall as the performance went on. The conventions of classical concerts we take for granted today—darkened venues, no talking during performances, restricted applause—when did these norms begin to take shape?

By Jeong-sun Ahn, music critic

The Emergence of Public Concerts Open to All Who Could Pay

During the Middle Ages, religious music prevailed, and the primary venues for musical performance were cathedrals and monasteries. However, during the Renaissance, royal courts and aristocratic salons started to become the center of musical activity, often with dedicated court musicians. By the late 17th century, however, public concert halls began to appear, shifting the focus from church and court to events geared toward the middle class.

In 1672, English violinist and composer John Banister (1630–1679) held a concert in his home in London. This is regarded as the first paid public concert on record. Admission was one shilling—the equivalent of a day’s wage for a laborer. Later in Paris, composer and oboist Anne Danican Philidor (1681–1728) launched the Concert Spirituel series in 1725. Admission cost 30 sols per person, making it accessible only to the more affluent. By the late 18th century, public concert culture had spread to German-speaking regions. In Leipzig, wealthy textile merchants invited talented performers for small private concerts. These events were held mostly at Gewandhaus concert hall, opened in 1781, and gave rise to the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra—still one of the world’s leading orchestras today.

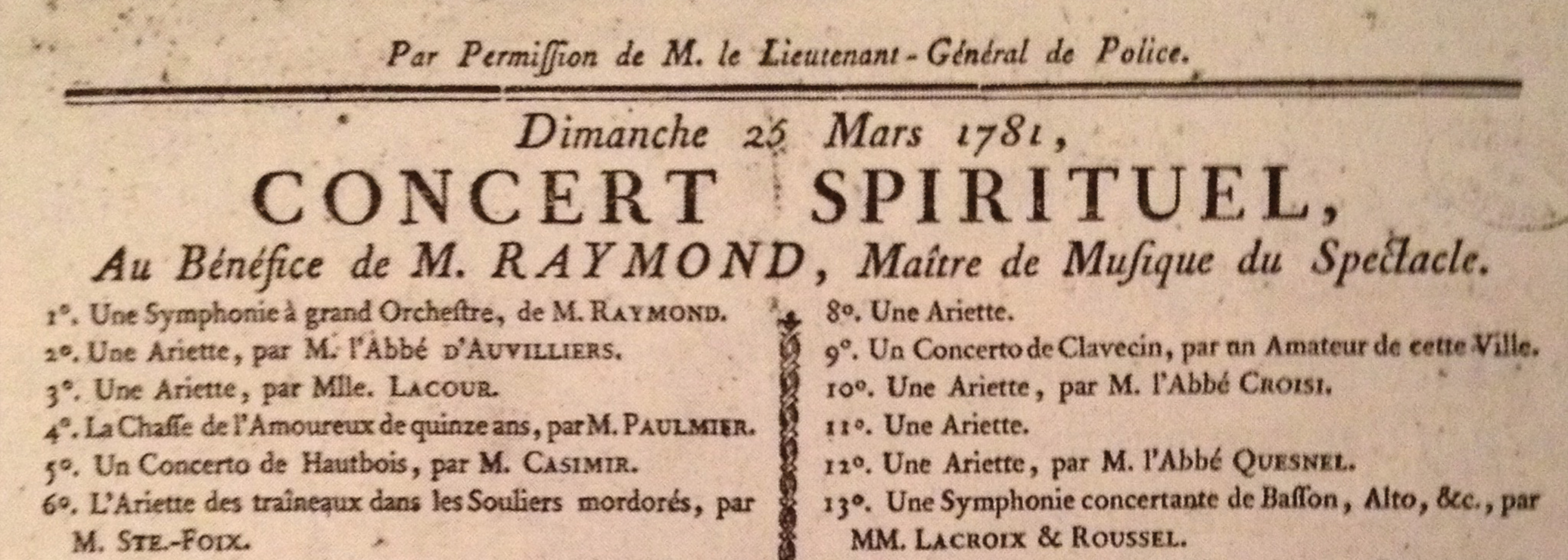

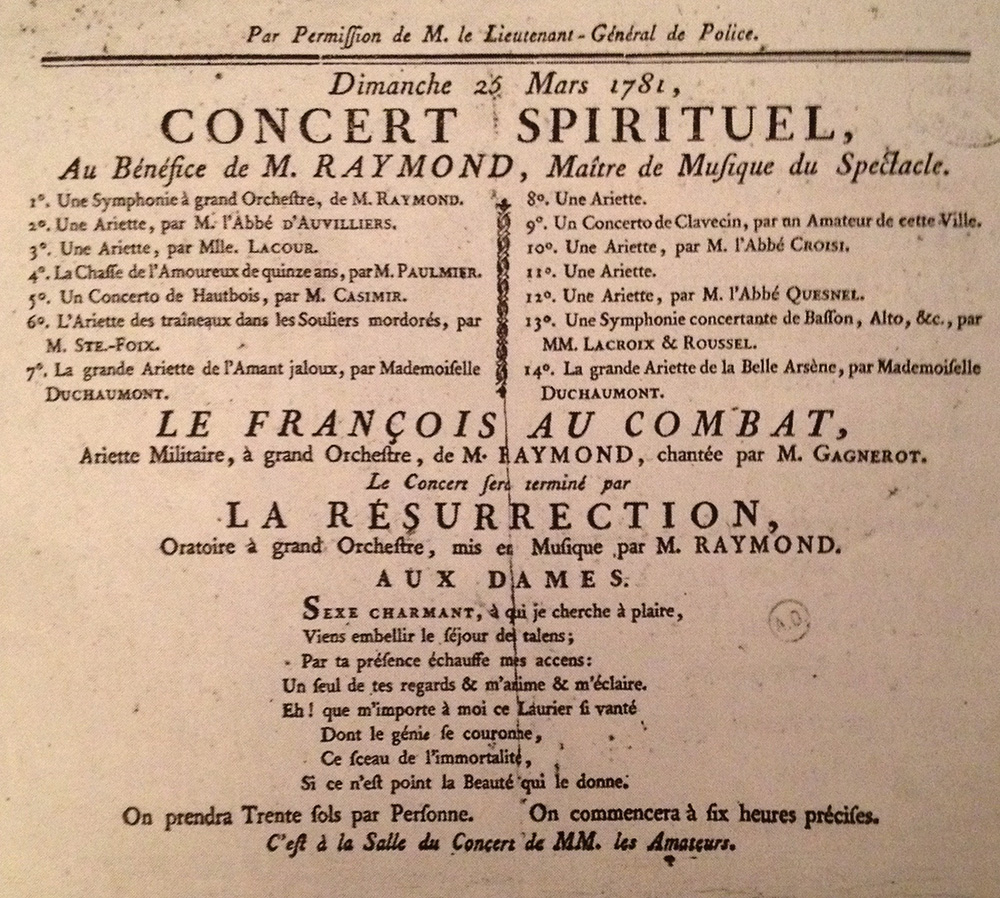

Poster of the 1781 Concert Spirituel

Poster of the 1781 Concert Spirituel

Public Concerts of the 18th Century: Venues for Socializing

In the 18th century, concerts were more than a philharmonic gathering—they were major social events. The audience listened attentively only when they were drawn to the music. Otherwise, they conversed or strolled about the venue. At opera houses or salon concerts, food and drink were often enjoyed. Musical immersion was not the primary focus for these early concert-goers, rather, they went for entertainment and social interaction. Performers and audience members interacted closely, with impromptu performances occurring frequently.

Looking at the 1781 Concert Spirituel program poster, we see a mix of symphonies, concertos, arias, and oratorios performed in a single event. These public concerts embraced variety, blending classical, traditional Korean music, pop, and musicals. Notably, performers’ names were listed for each piece, but composers were often omitted—except for M. Raymond—highlighting that performers, more than composers, were seen as the artistic focus of the time.

The 19th Century: Public Concert Halls as Sanctuaries of Artistic Sublimity

In the mid-19th century, the rise of railroads and urbanization allowed more middle-class audiences to attend concerts. With an increase in large-scale orchestral works, venues needed to grow in size and sophistication. This era saw the construction of major European concert halls: Leipzig’s Gewandhaus (1781, rebuilt in 1884), Vienna’s Musikverein (1870), the Berlin Philharmonie (1882), and London’s St. James’s Hall (1858), among others.

During this period, seating arrangement became rigid—aristocrats and the bourgeoisie claimed premium seats while the working class stood in cheaper sections. Audience behavior likewise transformed: talking during performances and moving around were prohibited, and listeners were expected to remain silent—even between movements. In short, the still, silent audience is a product of the 19th century.

Concert programs also evolved. Improvisation faded, and concerts were planned around specific themes, with faithful execution of composers’ scores becoming paramount. Performers shifted from being artistic protagonists to interpreters of the composer’s intent. Music performances grew more solemn and ritualized—akin to religious ceremonies. Richard Wagner, for example, banned applause during performances at Bayreuth and insisted that music be received reverently. From the mid-19th century onward, concert experiences became grand and sacred, especially with the rise of romantic aesthetics and the elevation of music as a sacred art form. Thus, public concert halls transitioned from spaces of social gathering to venues for elevated artistic experience.

Modern Concerts and the Changing Role of Public Music Venues

After the COVID-19 pandemic, the rise of online streaming, paid broadcasts, and virtual reality (VR) concerts reshaped how we engage with music. Physical concert halls became less central, while accessibility and personalized listening experiences expanded. The solemn concert etiquette born in the 19th century is now evolving, with some venues experimenting with more relaxed formats. For example, some allow movement and dining during performances, others offer guided concerts with commentary, or even interactive formats that incorporate audience questions and improvisation. These trends hark back to the social character of 18th-century concerts to once again become a space that bridges people-to-people connections.