in Story & News

The Search for

and Discovery of a New Tradition

- Writers and Painters of Moon-jang

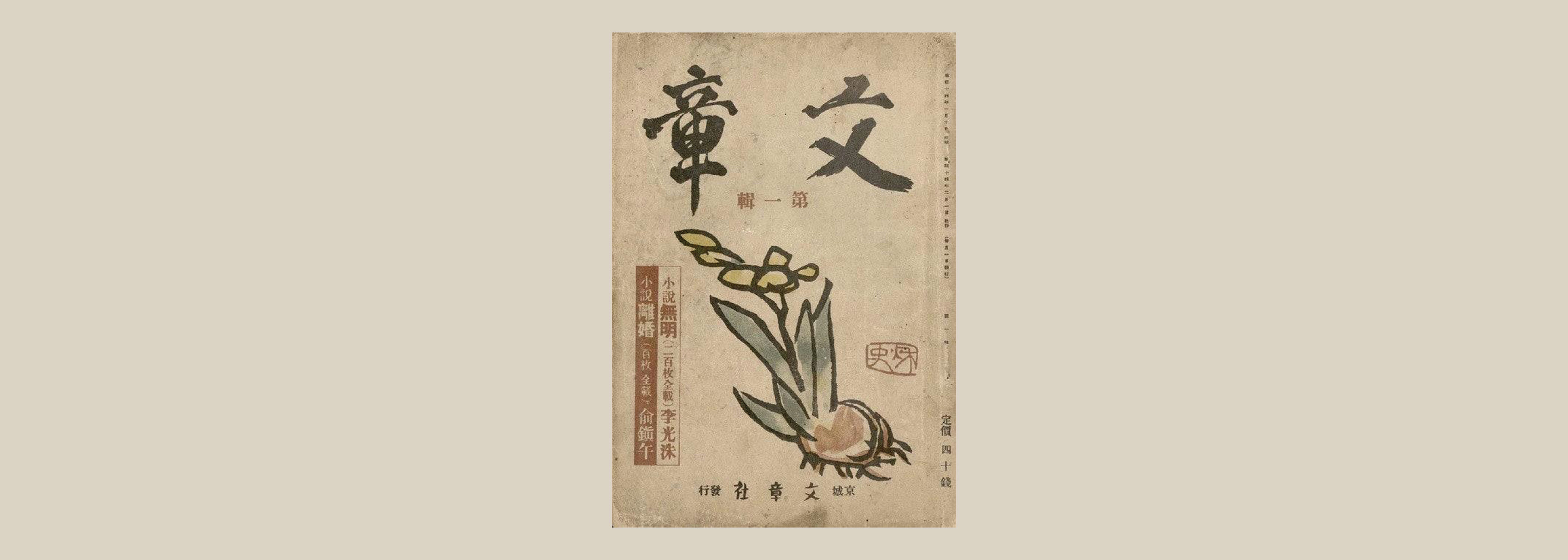

First published in 1939, Moon-jang holds a monumental place in the history of Korean literature. It was a platform where the foremost writers of the time—such as Ji-yong Jeong and Tae-jun Yi—published works that would leave a lasting mark on literary history. Moreover, it was the magazine that introduced significant post-liberation figures like Mok-wol Park, Chi-hun Cho, and Du-jin Park. The contributors to Moon-jang, who borrowed from the calligraphic style of the Joseon-era scholar Jeong-hui Kim and designed covers featuring his daffodil paintings, sought to illuminate the path forward for Korean art by invoking the concept of “tradition.”

By Prof. Jung-hwa Kang, Department of Korean Language Education, Korea University

Cover of the inaugural issue of Moon-jang, 1939.

An Era When Literature Dwelt in the Realm of Art

Literature evolved alongside the development of media. The rise of magazines and newspapers in the 1920s created the modern “reader” and transformed literature into a printed medium. With this new format that enables visual content consumption and physical retention, literature began to flourish in both depth and breadth. Unlike newspapers, which had to cater to mass audiences and were tied to commercial demands, magazines were often published by like-minded literary circles, giving rise to works that reflected a diversity of artistic philosophies. This new medium served not only as venues for literary publication but also as communal spaces where writers could engage with readers.

As a result, magazine covers became increasingly important—not just to attract readers, but also as a first impression that expresses the magazine’s identity. Writers thus began to collaborate with prominent contemporary painters who could visually articulate their artistic visions. Nam-seon Choe, who wrote the pioneering modern-style poem “From the Ocean to the Youth,” collaborated with Korea’s first Western-style painter, Hui-dong Go, for a cover illustration. Novelist Dong-in Kim co-founded the magazine Yeongdae with Chan-young Kim, a writer and painter educated at the Tokyo Academy of Fine Arts. The same trend applied to poetry collections and novels. Hye-seok Na, Korea’s first female Western painter, illustrated the cover of Sang-seop Yeom’s novel Gyeonuhwa. Meanwhile, the poet Sang Yi, who also worked as a painter, designed the cover of Ki-rim Kim’s poetry collection Weather Chart. These figures naturally mingled, shared artistic ideals, wrote poems and stories, and painted together. It was a time when literature and visual art moved as one.

The Guinhoe and Mokilhoe Circles

The 1930s hold special significance in the history of Korean literature and art. This was not only the period when modern literature began to take clear shape, but also a time of extraordinary cultural vibrancy. Among the notable developments were the activities of the Guinhoe in 1933 and Mokilhoe in 1934. Both groups were remarkable for clearly articulating their identity by not proposing any formal manifesto—pursuing instead a pure “art for art’s sake” philosophy. While Guinhoe published the magazine Poetry and Fiction, Mokilhoe held exhibitions under the name Mokilhoe-jeon. Though the members of these two circles worked in distinct artistic fields—literature and visual art—they actively exchanged ideas and shaped a shared artistic consciousness. Most importantly, they aimed to define the identity of Korean art by engaging with tradition. Ironically, their focus on tradition may have stemmed from a shared experience of studying abroad in Japan—a “modern space” at the time. There, they encountered Western literature and art, and this exposure deepened their contemplation of new artistic forms. Initially inspired by Western culture, they experimented with modernist poetry and Western painting. The more they absorbed Western art, however, the more they came to realize that tradition was the true path forward for Korean art.

Cover of the inaugural issue of Sonyeon, 1908.

Cover of the inaugural issue of Yeongdae, 1924.

The Most Universal Is the Most Korean

But how could something Korean also be the most global? Tae-jun Yi, a novelist and member of Guinhoe, expressed the idea in the following words:

Art, like dance or music, is said to transcend borders, but in the end, it doesn’t. (…) For Seung-hee Choi, Korean dance was the most natural form of expression. No matter how much Shalyapin might have practiced, he could never surpass Dong-baek Lee in singing Yukjabaegi. I believe that art, too, despite degrees of variation, is not entirely free of national boundaries. It is clearly easier for me to become Ohwon (Seung-eop Jang) than it is to become Cézanne or Matisse.

- Tae-jun Yi, “As Descendants of Danwon and Ohwon, Oriental Painting over Western Painting,” Chosun Ilbo, Oct. 20, 1937.

Tae-jun Yi argues that there exists an artistic form most suitable for us as Koreans. This is not merely an affirmation of the importance of traditional painting styles but a declaration of national pride—that even world-class opera singers cannot surpass Korean masters in native forms like Yukjabaegi1. In critiquing the Korean art world’s blind imitation of Western aesthetics, Yi illuminated an alternative path for Korean art.

It is worth noting that these artists believed Western art was already on a path that circled back to the East, and thus, they saw in traditional Korean art the potential for global relevance. The invention of photography had freed Western art from the obligation of faithfully reproducing objective reality. In moving toward abstraction and surrealism—toward the representation of inner, subjective worlds—Western art had begun to echo the spirit of East Asian painting, as the latter had never aimed to represent the objective world. Instead, East Asian painting emphasized expressing the artist’s mind—a concept closely aligned with Western Expressionism. Recognizing this parallel, these artists argued that Korean traditional art—especially literati painting—already embodied the subjectivity that Western art was just beginning to explore. Therefore, they asserted, the way to create truly global Korean art was through a continuation and reinvention of tradition.

- 1.A representative Korean folk song and musical style traditionally passed down in the southern regions of Korea, particularly around Jeolla Province.

Moon-jang and the Newness of “Tradition”

The members of Guinhoe and Mokilhoe, who had been active throughout the 1930s, eventually launched the literary magazine Moon-jang in 1939. They needed a platform to fully express their artistic vision. Their intentions are clearly revealed in the design of the inaugural issue: the title “Moon-jang” was created using the calligraphy of Jeong-hui Kim, a Confucian scholar from the Joseon Dynasty, and the cover featured a drawing of daffodils based on his painting. This choice signaled their commitment to grounding the magazine’s identity in the traditional arts of Joseon. However, simply appropriating the past amounts to regression. What allowed these artists to embrace tradition without falling into nostalgia was innovation.

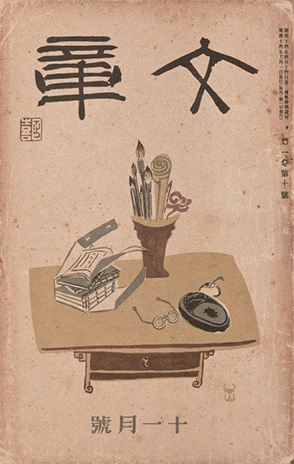

In an era shaped by modernization, many equated the West with progress. However, Moon-jang sought to rediscover modernity through tradition. The magazine identified the unfamiliar and novel not through imported styles but in the latent potential of traditional forms. Its covers and opening illustrations, which merged aesthetics of empty space and textual aesthetics of East Asian painting (ink, calligraphy, and brushwork) with the composition and techniques of Western art, hinted at a new kind of literati painting. These new literati paintings, which relied on the Four Treasures of the Study (brush, ink, paper, and inkstone) while incorporating Western compositional approaches, gave a fresh face to a fading tradition. In this way, rather than reverting to the past, the pursuit of newness through tradition offered a meaningful direction for artists exploring the identity of Korean art amid modernization.

During this period, literature and visual art deeply influenced one another, jointly raising the question of what constitutes Joseon art and helping lay the foundation for modern Korean aesthetics. The reason we, in the “here and now,” can present ourselves to the world through tradition is arguably because of the depth of thought and experimentation with tradition that emerged during this era.

Hye-seok Na, cover illustration for Sang-seop Yeom’s novel Gyeonuhwa, 1924.

Sang Yi, book design for Ki-rim Kim’s poetry collection Weather Chart, 1936.

Cover illustration of Moon-jang, November 1939.