in Story & News

In Search of Local Sentiment:

Centering on Paradise by Nam-soon Paik

Nam-soon Paik and Yong-ryeon Im, once celebrated as “Joseon’s treasured artist couple,” were artists who devoted their lives to exploring the essence of Korean art. Tragically, the Korean War destroyed nearly all of their works, and their names gradually faded into obscurity. But the recent rediscovery of Paik’s oil painting Paradise has brought renewed attention to their legacy. Through this rare work and writings left by contemporary literary figures, we revisit a question that defined their careers: What is Joseon art?

By Prof. Jung-hwa Kang, Department of Korean Language Education, Korea University

Paik, Paradise, 1936,

Collection of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

The First Artist Couple to Hold a Joint Exhibition

On November 5, 1930, the Dong-A Ilbo building in Seoul buzzed with anticipation. Crowds gathered for the debut exhibition of a painter couple who had achieved acclaim abroad. A total of 82 works, including 20 croquis, were on display. At the time, very few Korean artists had studied Western painting abroad, and most of them chose to train in Japan. That this couple had studied in France and the US, the very heartlands of Western art, made the exhibition a cultural event of national significance.

Im began his art education in China, later attending the University of Chicago and graduating with distinction from Yale, where he was selected for a study tour of France. It was there that he fatefully met Nam-soon Paik, who had already drawn attention as the first Korean woman to study art in France. At the Salon des Artistes Tuileries, Paik’s works were selected to be exhibited, signaling her emergence as a painter of international caliber. The two married in the picturesque French village of Herblay and returned to Korea that same year, where they presented their first joint exhibition. The press celebrated them as “Joseon’s treasured artist couple,” and articles lauding their talents filled the pages of Korean newspapers. In the dark years of Japanese colonial rule, the couple—“global artists born of Joseon”—offered a rare source of pride and hope to fellow Koreans.

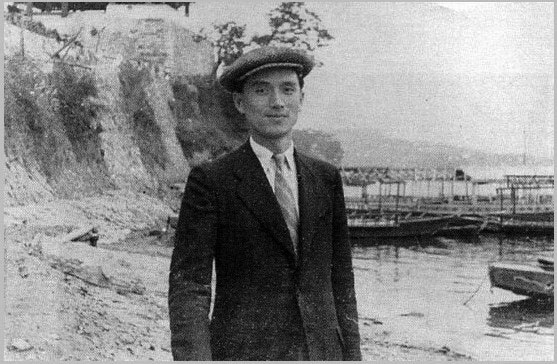

Im and Paik, Joseon’s treasured artist couple

Filling the Silence with Words

The Im–Paik couple made a dazzling entry into the Korean art scene of the 1930s and remains an important chapter in the history of modern Korean art. And yet, despite their fame at the time, they remain little known to the public today. This is particularly true of Nam-soon Paik. Though she was a pioneering female artist of the first generation and remained highly active throughout her career, little scholarly work has been devoted to her artistic legacy. The main reason is the tragic loss of their work. Most of the couple’s oeuvre was destroyed during the Korean War, and only two or three confirmed pieces are known to survive beyond a few catalog reproductions. Considering that they were once hailed as treasures of modern Korean art, the loss is all the more regrettable.

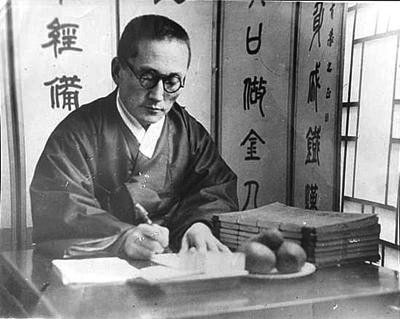

Even so, it is possible to glimpse their artistic world through surviving art criticism from their time. Before the 1950s, Korea had no professional art critics. Literary figures often filled the role. Among them was Gwang-su Yi, one of the most influential writers of the era, who attended the couple’s joint exhibition and left behind his impressions.

Gwang-su Yi, published a review titled “Im Couple’s Exhibition: Impressions of an Amateur Viewer” in Dong-A Ilbo on November 9, 1930. It was one of only three surviving pieces of art criticism he ever wrote—alongside A Spectator’s Impression (1928), about painter Jong-woo Lee’s solo exhibition, and Tokyo Sketches: Notes from the Ministry of Education Art Exhibition (1916).

For Gwang-su Yi, who believed that the Korean people urgently needed cultural heroes, these three exhibitions represented the emergence of artistic pioneers. Introducing Korean artists who had gained recognition in Japan, America, and France to the domestic public offered hope in a time of colonial oppression. In a nation shrouded in darkness, their stories were a much-needed source of light.

With most of their works lost, Gwang-su Yi’s review offers rare insight into what Im and Paik’s paintings might have looked like. According to his account, Im’s work evoked an “Oriental” sensibility, leaning toward an Indian aesthetic, while Paik’s work had a “light and Latin” air. Gwang-su Yi, also offered impressions of individual pieces, allowing us to imagine the visual character of their now-vanished art.

Gwang-su Yi’s interest in Paik and Im’s exhibition was not merely due to their overseas training. He recognized in their work the potential for Korean art to gain international recognition, and believed that such achievement could foster a sense of national pride through art, even under Japanese colonial rule. His critique was not simply an appreciation of their paintings—it was part of a broader artistic discourse that sought to define the future direction of Korean art.

Gwang-su Yi, was not the only literary figure to write about Paik. Another critic, Tae-jun Yi—also a writer and art reviewer—commented on Paik’s entries in the Joseon Art Exhibition. He noted a lack of vitality in her work, citing awkward use of perspective and a failure to capture the natural flow of water. But such criticisms stemmed largely from a misunderstanding of Paik’s unique stylistic approach. Her art existed in the liminal space between Western and Eastern paintings, and therein lay its distinctiveness.

These two are people of the future, not of the past. Because they believe in the boundless possibilities of progress, they must hold steadfast to their love for Joseon and endure the hardships of the artist’s path. And they must possess the ambition never to be content with small achievements.

- Gwang-su Yi, Im Couple’s Exhibition: Impressions of an Amateur Viewer

Writer Gwang-su Yi, who viewed and reviewed the couple’s exhibition

Writer Tae-jun Yi, who critiqued Paik’s work

Searching for Local Sentiment in the Harmony of East and West

Having studied in both the US and France—the epicenters of Western art—Paik and Im were uniquely positioned to engage deeply with the question of tradition. Their experience as Asian artists in foreign cultural contexts sharpened their awareness of identity and enabled them to reimagine the direction of Korean art.

The couple’s conscious consideration of tradition is evident in their involvement with the Mokilhoe art society. Mokilhoe sought not merely to imitate Western styles but to discover and express what it called “local sentiment.” This idea was not limited to traditional subjects or motifs—it was a dynamic approach that integrated emotional and cultural authenticity with the spirit of modernity. For Paik, who actively pursued this philosophy as a Mokilhoe member, the search for local sentiment was a creative and spiritual imperative. Her art reflects this pursuit.

Paik’s Paradise, spotlighted as a “rare masterpiece” in the 2021 release of the Kun-hee Lee Collection, is a monumental work in the format of an eight-panel folding screen, measuring 166 by 366 centimeters. Miraculously preserved through the chaos of war, it remains the only surviving modern work by Paik, offering a rare opportunity to see what once only existed in text and memory. What makes Paradise remarkable is its synthesis of Eastern and Western art traditions. While it follows the compositional logic of classical East Asian landscape painting, it also includes unmistakably Western elements such as palm trees and partially nude figures. Visually, the work adopts the format of a traditional Korean folding screen, yet it is executed entirely in oil paint. In this, Paradise stands as a bold attempt at East-West fusion. The critiques made by Tae-jun Yi—particularly his remarks about the lack of dynamic flow or inconsistent perspective—can be better understood through this context. Paik was following the compositional principles of Asian landscape painting, where conveying the spirit or emotional truth of a scene takes precedence over optical realism. Her work drew on Western methods without abandoning a distinctly Korean sense of beauty. In doing so, she laid the groundwork for an original artistic vocabulary at the intersection of tradition and modernity, of East and West.

Im’s 1930 painting of Herblay, the village where he married Paik

Paradise as a Vision for the Art of “Us, Now”

Paik’s artistic vision offers timely insight for contemporary Korean art. Instead of merely replicating tradition, she sought harmony between inherited aesthetic sensibilities and modern expression, and in doing so, set a powerful precedent for today’s artists navigating the fusion between tradition and modernity. In particular, Paik’s sense of balance deserves renewed attention in the ongoing effort to articulate a distinct identity for Korean art in the global art market.