Opportunities in the Quantum Computing Sector

The Changes and Opportunities

Quantum Computers Will Bring

Since the UN officially declared 2025 as the “International Year of Quantum Science and Technology,” commemorative events have been held worldwide. Major global companies are racing to announce news related to quantum computing, and the resulting flurry of media coverage reflects the rapidly changing state of investment in this field. How exactly do quantum computers differ from traditional digital computers, and will they truly bring about changes that surpass the digital revolution? While our government, together with academia and research institutes, is implementing policies and securing budgets to catch up with leading quantum information technology countries like the US and China, Korean companies have yet to show significant movement. If our companies fail to step up, the talent and technology we are developing will end up benefiting others.

By Jae-wan Kim, Distinguished Professor at Quantum Universe Center, Korea Advanced Institute for Advanced Study

The First Quantum Revolution: Is Quantum Science and Technology Just Emerging Now?

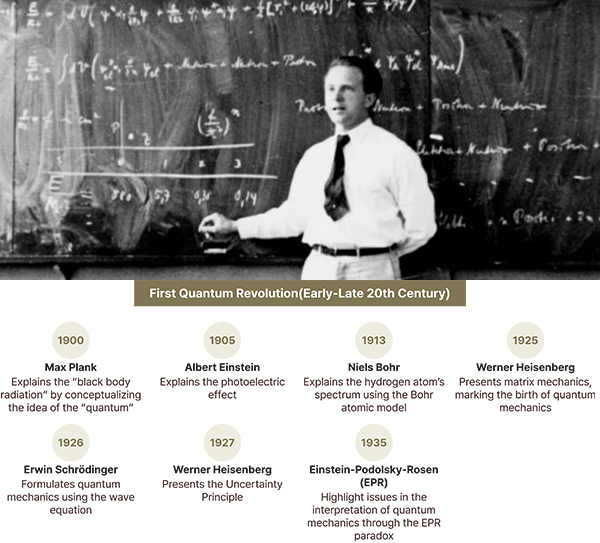

Although the UN declared 2025 the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology to mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of quantum mechanics, the term “quantum” was first introduced in 1900 by Max Planck. During the Industrial Revolution, there was a need to understand the temperature of heated metals. As metal temperatures rose, they changed color from black to red, then yellow, and eventually white—a phenomenon known as “black-body radiation.” Existing physics theories at the time couldn’t explain this. Planck hypothesized that the energy of light was not continuous but came in discrete packets, which could be counted individually. This assumption successfully explained black-body radiation. In 1905, Albert Einstein applied the same idea to explain the photoelectric effect—the phenomenon in which light striking a metal surface causes electrons to be ejected. This introduced the concept of light energy as a particle-like bundle, which later became known as the “photon.”

In 1913, Niels Bohr explained the spectrum of the hydrogen atom by proposing that electrons orbiting the nucleus do not move along continuous paths but instead occupy discrete, separate energy levels. He proposed that electrons emit or absorb light when they jump between these orbits. This concept of a sudden leap between states became known as a “quantum jump”—a term now more commonly used in business to describe a sudden, significant change. Thus, the term “quantum” came to represent the idea that energy and various physical quantities at the atomic and subatomic level exist in discrete, quantized units rather than continuous flows.

In 1925, Werner Heisenberg introduced matrix mechanics—using matrices to represent physical quantities—to provide a more precise explanation of the hydrogen atom. This marked the formal birth of quantum mechanics, which serves as the background for the UN and UNESCO designation of 2025 as the centennial year for the birth of quantum mechanics.

In 1926, Schrödinger developed de Broglie’s matter wave theory into the form of a wave equation, laying the foundation for quantum mechanics. In 1927, Heisenberg proposed the uncertainty principle, which states that it is impossible to simultaneously determine with absolute precision the position and momentum of a particle.

This introduced the “measurement problem” in quantum mechanics. In classical physics, physical systems were believed to change deterministically according to laws of nature, and measurement was considered merely reading out a pre-determined value. In contrast, Bohr and Heisenberg argued that the state of a quantum system is not fixed until a measurement is made, at which point one of the possible superimposed states is probabilistically selected. Einstein, despite his major contributions to the development of quantum mechanics, could not accept this indeterministic and probabilistic interpretation. He famously objected by saying, “God does not play dice,” and when told that a state is determined by measurement, he countered, “Do you really believe that the moon ceases to exist when no one is looking at it?”

In 1935, Einstein, along with Podolsky and Rosen, published a famous paper known as the “EPR” paper, challenging the interpretation of quantum mechanics. They posed the question: If two entangled particles are separated and one is measured, would that measurement instantaneously affect the state of the other particle? If so, wouldn’t this violate the principle of special relativity, which states that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light? This phenomenon was later termed “quantum entanglement.”

Schrödinger also highlighted the paradox of quantum mechanics with his famous thought experiment involving a cat that is simultaneously alive and dead in a superposition state. When two degrees of freedom in a physical system are correlated in a superposition state, they are said to be “entangled.” In Schrödinger’s cat experiment, the cat and the radioactive isotope are entangled.

Even though the measurement problem remained unresolved, physicists used quantum mechanics to understand the world and develop new technologies. The periodic table, built on centuries of empirical evidence, was explained by quantum mechanics, leading to an understanding of molecular structures and the synthesis of new materials. This progress enabled the creation of semiconductors and lasers, sparking a “digital revolution” in the late 20th century through advancements in nanotechnology. This phase of applying quantum mechanics to hardware—the physical aspects of information storage and processing—is known as the “First Quantum Revolution.”

The Second Quantum Revolution: Advancements in Quantum Information Science and Technology

While the First Quantum Revolution was progressing, some physicists remained curious about the measurement problem. In 1964, John Bell proposed an inequality that could experimentally test whether Einstein’s concerns in the EPR paper were valid or whether quantum mechanics’ predictions were correct. John Clauser in the 1970s, Alain Aspect in the 1980s, and Anton Zeilinger after the 1990s conducted experiments that confirmed the predictions of quantum mechanics. For their work on quantum entanglement, Clauser, Aspect, and Zeilinger were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2022. The fundamental principles of quantum mechanics—superposition, entanglement, and measurement—became the foundation for quantum cryptography and quantum computing. Quantum mechanics, which had initially been confined to hardware, was now applied to software and operating systems, ushering in the “Second Quantum Revolution.”

Statements such as “Nobody understands quantum mechanics” or “Even Einstein couldn’t understand quantum mechanics” are outdated or simply incorrect. While fields like string theory and quantum gravity remain highly complex, the quantum mechanics used in quantum information technology is not particularly difficult. Einstein had a deep understanding of quantum mechanics but could not accept its probabilistic interpretation. His persistent challenges led to the EPR thought experiment, which ultimately deepened the understanding of quantum entanglement and sparked the Second Quantum Revolution.

Digital technology represents information using bits (0s and 1s). Four bits can represent 16 possible states (0000 to 1111), but a classical processor must handle each state separately. Quantum information, however, uses qubits, which can exist in a superposition of both 0 and 1 simultaneously. Therefore, four qubits can represent and process all 16 states at once. As the number of qubits increases, the amount of information that can be processed grows exponentially—this is called “quantum parallelism.” In classical computing, adding processors result in a linear capacity increase, but quantum computing scales exponentially, creating a vast potential for computational power. However, since quantum information must be stored in delicate systems that are easily disturbed, developing quantum technology requires more sophisticated techniques than those used in digital technology.

The 2023 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics was awarded to theoretical scientists who contributed to the Second Quantum Revolution: Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard for inventing quantum cryptography, David Deutsch for proposing quantum parallel algorithms, and Peter Shor for inventing the quantum factorization algorithm. Shor’s algorithm, published in 1994, demonstrated that a quantum computer could factor large numbers exponentially faster than a classical computer, igniting global interest in quantum computing.

In the late 1990s, when research into superconducting circuits had almost vanished in South Korea, Yasunobu Nakamura and his team at NEC in Japan created the first superconducting qubit. In 2001, Isaac Chuang at IBM achieved the first quantum factorization using a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) quantum computer—though it factored only the small number 15, it generated significant interest in quantum computing.

The quantum mechanics needed to build quantum computers is not particularly difficult, but implementing the technology is extremely challenging. It requires a high level of fundamental scientific understanding. For their pioneering work in experimental quantum physics, Serge Haroche and David Wineland received the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics. Research in quantum optics, atomic physics, and superconductivity continues to support the advancement of quantum information science.

Quantum Computers: Turning the Impossible into Possible

Quantum computers are expected to surpass classical supercomputers not just slightly, but by orders of magnitude. Simulating a system of 100 electrons would require handling 2^100 or 10^30 (a thousand trillion trillion) data points—impossible for classical computers. In the early 1980s, Richard Feynman proposed that computers themselves should be quantum in nature to simulate quantum phenomena efficiently. Classical computers require resources that scale exponentially with degrees of freedom, but quantum computers need only linearly increasing resources. Quantum computers are anticipated to have enormous value in drug and materials discovery, artificial intelligence and machine learning, and optimization problems in fields like transportation and finance, potentially creating trillions of dollars in economic value.

Despite the potential, quantum computers still have a long way to go. While some are highly optimistic and others are skeptical, the focus has shifted from “if” quantum computers will work to “when” they will work. In late 2024, Google demonstrated quantum error correction with its “Willow” quantum computer, solving a problem in five minutes that would take the world’s fastest classical computer longer than the age of the universe. IBM has developed a system for linking multiple quantum computers, opening the path to scalability and increasing the number of qubits from the current 100–1,000 range to much higher levels. However, so far, quantum computers have not solved any practically useful problems that classical computers cannot handle. Still, recent breakthroughs—such as IBM’s 16-qubit quantum computer identifying a pancreatic cancer drug target—offer hope for practical applications.

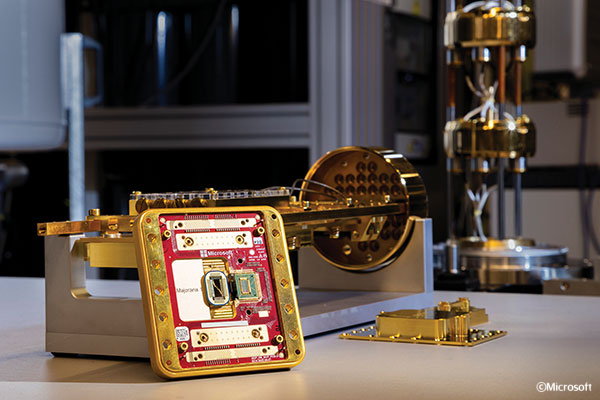

Quantum computing chip Majorana 1 unveiled by Microsoft in February

Quantum computing chip Majorana 1 unveiled by Microsoft in February

“Quantum computers are anticipated to have enormous value in drug and materials discovery,

artificial intelligence and machine learning,

and optimization problems in fields like transportation and finance,

potentially creating trillions of dollars in economic value.”

The US-China Quantum Race and South Korea’s Response

China has developed a 2,000 km quantum encryption network between Beijing and Shanghai and conducted satellite-based quantum communication using the Micius satellite. It has also developed quantum computers like Zuchongzhi and Jiuzhang. The US has designated quantum technology as a strategic technology and imposed sanctions on Chinese companies involved in quantum development. South Korea lags behind leading countries in quantum information technology. However, in 2023, the government introduced the “Quantum Science and Technology and Industry Promotion Act,” allocating several hundred billion won over the next eight years.

The government is prioritizing workforce development, establishing three quantum graduate schools nationwide. Training new talent will take over five years, but South Korea has an abundance of experienced scientists and engineers who can transition into quantum technology through short-term retraining programs. In fact, many professionals working in the quantum computing industry in the US and Europe have transitioned from other related fields. While universities, government-funded research institutes, and the government are actively engaging in quantum technology development, South Korean mid-sized companies have remained largely silent. If domestic companies fail to engage, trained talent and developed technology may flow overseas.

In the early stages of technological development, creating the technology is crucial; however, in the mature stage, leveraging that technology creates greater value. Although South Korea may be behind in quantum computer development, the country can steadily advance basic science and technolologies in anticipation of utilizing quantum computers to drive future industrial development.